Archaeologist Geoff Emberling sees the beauty in a culturally diverse land that has yet to be fully understood

Geoff Emberling, guest curator of the exhibition “Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa” on view at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), has directed excavations in Sudan where he uncovered Kerma period sites now flooded by the Merowe Dam. He recently spoke with me about the show and why he finds Nubia so interesting.

Shawabti of King Senkamanisken, Nuri, tomb of Senkamanisken, 640–620 B.C.

EBM: Why do we know so much today about ancient Egypt but not about Nubia?

GE: There are a number of different reasons why Egypt is better known. Egypt is a literate civilization, so it’s more expressive in that sense. And the preserved, standing remains of Egyptian temples are larger, more impressive, for the most part. Also, Egyptian tomb painting provides an incredible amount of detail and specificity that is difficult to get for many periods of Nubian history. So there’s an undoubted difference in the nature of the historical record.

Another reason, I think, is tied up with the history of racism, both in society, more broadly, and within academia, in particular. This is, I would say, not a problem today, but it has informed the decisions and perspectives that people have had on these civilizations. The ugly truth is that through much of the 20th century, scholars thought of Nubia as an “African” civilization and explicitly excepted Egypt from being part of the greater African tradition—despite the fact that Egypt is within the continent of Africa. So as an African civilization, Nubian cultures were deemed less interesting, less complex, less powerful, and therefore less worthy of the kind of detailed archaeological attention that Egypt has had.

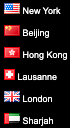

Hathor-headed crystal pendant, El-Kurru, 750–720 B.C.

EBM: So what changed and when?

GE: It’s certainly the case that there’s now a critical mass of archaeologists working in Nubia broadly; that is, in southern Egypt outside the Nile Valley—because that part of Nubia is underwater—but also in northern Sudan. There’s a critical mass that has been working now for several decades and starting to really produce detailed syntheses and new interpretive perspectives. Among the results of this intensified work is the finding that in some periods, for example the Kerma period [ca. 2500–1500 B.C.], Nubian civilization is now known to have been considerably more militarily powerful than previously thought. That is, that they seriously threatened the Egyptian state with raid and conquest.

But to answer your question of what changed and when, there is a long history that began in the 19th century with efforts of some Europeans to outlaw the slave trade, specifically from Sudan. That was part of the political motivation for British colonialism in Sudan—trying to stop the slave trade. It has taken a long time for those values to be changed. I have had people ask me to confirm that, “Egyptians were white, right?”

Head of a Nubian, Kerma, 1700–1550 B.C.

EBM: Were any Nubian excavations affected by the recent uprising in Egypt? Were any digs disrupted and do you know of any looting at Nubian sites?

GE: There was no looting that I know of. Archaeologists are more concerned about the ongoing construction of dams in Sudan that are threatening to flood even more of Nubia than is already underwater.

EBM: What interests you most about Nubia?

GE: For me, archaeology is at its best when we make discoveries that give us a picture of a time and a place so different from our own that we get a sense of broader context for our own historical moment and social and political realities. From that point of view, Nubia is really interesting as a distinctive kind of social and political organization. One way it’s distinctive, for example, is how kingship is handed down. It didn’t go father to son; it went in a pattern that we still don’t completely understand—from father to son, to other son, then to the next generation. Part of this succession involved marriage between kings and their sisters. It also involved a surprisingly prominent role for female members of the royal family. So unlike at least stereotypical views of ancient societies, in Nubia we suspect a greater role for women and political power than in some others.

Fly pendants, Semna, 1550–1070 B.C.

EBM: What, specifically, is known about the role of women?

GE: We know that at some times they ruled independently. This is expressed more directly in the later Nubian tradition, after about 350 B.C. In classical sources, there are references to having to fight against a Nubian queen who was militarily powerful—and she only had one eye. Apparently, she was one tough broad! And that’s a later incarnation of something that we glimpse, less vividly, in earlier periods. But in the royal cemeteries of Nubia, most of the burials are burials of queens, simply because kings married multiple times, and so there were more queens running around than there were kings. But they all got royal burials.

EBM: What does a typical royal burial contain?

GE: This points to another reason I find Nubia so interesting. Egyptian cultural practices are adopted in selective and interesting ways in Nubia. So earlier Nubian royal burials, which we know from the site of Kerma, are very non-Egyptian. Nothing about them is Egyptian. The rulers were buried in huge mounds, and in the most powerful of these burials, hundreds of retainers were buried in the tumulus and thousands and thousands of cattle skulls were buried around the base of the mound, indicating the funeral feast but also the wealth of the king.

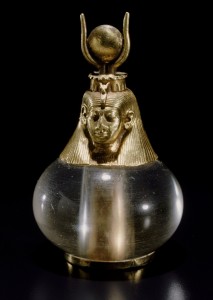

Statue of King Senkamanisken, Gebel Barkal, 640–620 B.C.

EBM: So that would just be for a king’s burial then, not for a queen’s?

GE: It’s difficult to be certain because these burials were looted in such a way that there are no bones preserved in the central burial chamber. But it is normally assumed that these were burials of kings. But now that you mention it, I don’t think that there’s any evidence, I mean, it’s not like there are any inscriptions that name the original occupants of these early burials.

EBM: Were the Egyptians and Nubians similar in their daily lives?

GE: Actually, in a lot of ways, they were not. This to me, again, is something that’s interesting about Nubia—it’s a different kind of society in ways that we have yet to fully understand. Egypt was a relatively bureaucratic and urban civilization, even though people sometimes say Egypt was “a land without cities.” This is no longer considered to be the case. Nubia, for the most part, was non-urban. Its population was quite dispersed. There was probably a significant degree of mobility practiced by most Nubians.

Nubia was also a culturally diverse land. The term Nubia itself is a very late term. It’s a Greek term, actually, and it seems to refer to a tribe called the “Noba” who really only appear in the historical record in the third century B.C. So when we talk about the “land of Nubia,” there’s a natural inclination for us to think in terms of a unified culture but, in fact, nothing could be further from the truth. It’s fragmented with a lot of different cultures and—to the extent that we can identify various places—there are a lot of different little polities and, presumably, different cultures that are involved throughout Nubia.

Painted cow skull, Khozam(?), 1700–1550 B.C.

EBM: How much is known about the individual cultures?

GE: One thing that we know is a series of place names. This points back to the difference between the Egyptian record and the Nubian record. There is an Egyptian trader named Harkhuf who traveled through the lands of Nubia [ca. 2250 B.C.]—but he didn’t use the word Nubia. He described different places that he visited and he used terms for them that are, in some cases, difficult to locate exactly. One place, the most certain, is Wawat, which is between the second and first cataracts. It’s not clear where all the other places are, but it’s clear that most of them fall within the area that we would call Nubia today. So it just points out that politically there’s a lot of division. Culturally, it’s also clear that there are some divisions, for example, looking at archaeological ceramics. It’s always difficult to be certain when you’re starting with archaeological finds exactly how this plays out—ethnicity, tribal identity, anything like that. But Nubia as a whole is rarely unified by a single ceramic style.

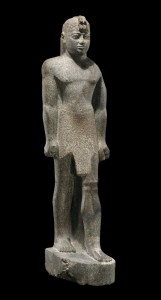

Straight-sided redware bowl, Nubia, 3100-3000 B.C.

EBM: What is your favorite object in the show and why?

GE: I just love the ceramics. They’re handmade, many of them are probably made by women in their households, they’re decorated in elaborate geometric ornamentation in forms that are deeply evocative of the natural world—shapes like gourds and ostrich eggs—and so for me, the ceramics are gorgeous. But it’s hard to turn your back on the grandeur of the royal statue of Senkamanisken, a Nubian king.

EBM: What do you hope visitors get out of the exhibition?

GE: I’ve written a narrative for this show, trying to work against the way in which we have a tendency to see Nubia through Egyptian eyes. So what I hope people will see is that Nubia is a rich and interesting culture in its own right that is fully deserving of our attention—and that attention is rewarded with insights into life in a very different time and place.

For more on the exhibition, including commentary by Jennifer Chi, associate director for exhibitions and public programs at ISAW, see Through Nubian Eyes, Part I.

“Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa” in on view at ISAW through June 12, 2011.