A photo exhibit leads to the door of the AMNH gift shop, offering passersby a snapshot of the Inca highway

Wiñay Wayna's terraces may have been used to grow coca, which the Inca used in rituals.

In a narrow corridor on the first floor of the American Museum of Natural History—a short flight down from the hubbub surrounding the towering Barosaurus in the main entrance lobby—photographs of lush emerald landscapes, thick adobe walls, snaking muddied rivers, and snow-capped mountaintops brighten up the institutional-white walls. Many visitors stop, look, snap pictures with their phones, and continue on to the gift shop. But those who read the gallery wall labels are rewarded with information about the remains of a startlingly vast, timeworn network of wobbly suspension bridges, dirt-covered pathways, and paved trails that crisscross the exhilarating vistas of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. The exhibition “Highway of an Empire: The Great Inca Road” brings together more than 50 photos of points of interest along the impressive network, which at its peak spanned a remarkable 25,000 miles. (To put that into perspective, the equatorial circumference of the Earth is 24,901.55 miles.)

It is believed that between about A.D. 1400 and the 1530s, the Incas both constructed new imperial routes and incorporated previously existing road systems of annexed states and empires. “The ‘Inca road’ is a diverse concept,” says R. Alan Covey, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University, who was brought on board to curate the show. “In some highland regions, they may have rehabilitated roads used by the Wari state [A.D. 600–1000], and on the coast, they may have mapped onto routes of states like Chincha and the Chimú.”

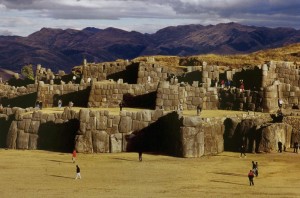

The Inca gathered at sites such as Sacsayhuaman to take part in festivals and religious rites.

The road system facilitated the movement of people—soldiers, administrators, messengers, and those on state business—as well as information and products. “Goods like corn and dried potatoes were moved up to highland administrative centers and to outposts on the highway, while exotic raw materials and fine craft goods were transported to Cuzco, the Inca capital,” says Covey. “The main Inca networks were designed to maintain order, and not for ‘public’ use.”

The Inca road has been explored and documented by researchers, including archaeologist John Hyslop who published an authoritative book on the qhapaqñan (royal highway) in 1984. Over the past few years, more than 300 participants from the Andean nations have surveyed some 9,000 miles of the road, documenting archival descriptions of routes from the early Colonial Period and carrying out more intensive research at sites found along or near it. While parts of the road are well preserved, others have been destroyed or replaced by modern routes. A goal of the project is to have the Qhapaq Ñan, the Main Andean Road, recognized on the UNESCO World Heritage List so it will be preserved for future generations. It is currently on the Tentative List.

A traveler takes in the view from the Inca road near Machu Picchu.

While the road is undeniably impressive, it’s the fine quality of the photos that first draws viewers into each scene. Taken by more than a dozen accomplished contemporary photographers, the vivid prints are mounted on stark-white mat boards in uniform, straight-edged black frames. This allows for bold colors—such as the red poncho of an ethereal figure amid wispy clouds on a stone-slab road near Machu Picchu—to radiate from the image. “For me, the Andean landscapes are breathtaking,” says Covey. “There is a certain artistry in how some of the Inca roads traverse such diverse panoramas. I think that combination of natural and constructed beauty is really impressive and the photos really bring it out.”

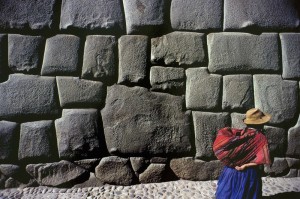

Inca craftsmen at Cuzco shaped massive blocks with hammers made of hard river stones.

One standout shot shows a woman in a flowing blue skirt and straw hat balancing a red cloth bundle slung over her back. She follows her shadow toward a sundrenched wall of irregularly shaped gray stone blocks, and is no taller than three of them stacked up; the stones likely continue well beyond the reach of the shot, but how far? The photo is cropped tightly, making it impossible to see where the wall—an Inca ruler’s palace at Cuzco—begins or ends, both punctuating its monumentality and providing testament to the level of Inca stone craftsmanship also seen in the road system. A shot of Sacsayhuaman (second image from the top of this page), a site used for festivals and religious rites, has a similar effect: tourists exploring the fortress-like structure look more like ants against the backdrop of imposing walls, mountains sprawling as far as the eye can see, and, possibly, an impending rainstorm.

Mummy bundles of the Chachapoyas, who were conquered by the Incas, were found on a cliff near the road in 1996.

The exhibition also highlights the broader story of Inca society through photos of the Andean landscape where herders, farmers, and fishermen made a living before, during, and after Inca times. The story of these people is inextricably linked with the road. “The Incas used llamas as pack animals, but couldn’t ride them,” says Covey. “So the breadth of the road system—from central Chile to southern Colombia—is made all the more impressive when one considers that it was traversed on foot.”

“Highway of an Empire: The Great Inca Road” is on view at New York’s American Museum of Natural History through September 2011.